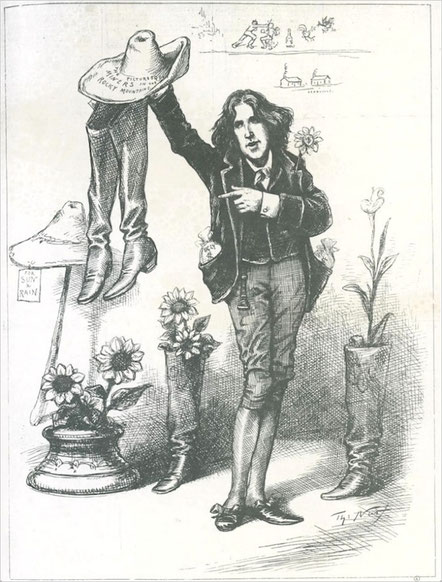

Oscar Wilde spent a full year in North America, but according to this cartoon his only idea of what to do with cowboy boots was to use them as flower pots.

What is it?

A biography of Oscar Wilde by Richard Ellmann, first published in 1987. It’s considered the “standard” biography of Wilde.

Don’t all gay men already know all about Wilde’s life?

No. I think we may think we know the main points, but I discovered so many surprising facts through reading this biography. Among them: Wilde had a lifelong fascination with Roman Catholicism, and even had an audience with Pope Pius IX; Wilde’s first homosexual experience didn’t take place until he was in his thirties, married, and a father; he actually gave a lecture in my hometown (Belleville, Ontario) in 1882!

But is Wilde still an important figure for gay men? We’ve moved on, haven’t we? Does his life have anything to say to us in 2019?

Thankfully, we have moved on: no one in any developed country nowadays is going to be sentenced to two years’ hard labour for having engaged in homosexual activity. But I come away from reading this magisterial biography with a deepened sense of Wilde’s importance in gay history. In so many ways, his life is symbolic, for good and bad. His fate is an archetypal gay nightmare: being publicly outed and thrown in prison, and then being more or less abandoned by everyone on his release. And Lord Alfred Douglas has got to be the epitome of the nightmare gay boyfriend, the succubus who utterly destroys the one who is seduced by his beauty.

Wilde also offers a timeless cautionary tale about the tendency of homosexual men to be excessively self-regarding. Although an infinitely more complex and thoughtful man, he does remind me of Quentin Crisp, whose autobiography I recently read. Wilde has the same tendency to be utterly fascinated with himself. This is no doubt related to the gay person’s consciousness of being different, and of having to rely upon himself emotionally. Still, the pitfalls of this behaviour are even more evident in Wilde’s life than in Crisp’s. Wilde’s last few years are absolutely miserable, and one can’t help but feel he didn’t do much to help himself. (His wife, always sympathetic to him, commented that his greatest problem was his inability to understand that there are other people.)

It sounds as though you came away from this book with mixed views of Oscar Wilde.

He was a fascinating, incredibly complex figure, and from all accounts immensely kind and generous. I find him so puzzling, though, even after reading a 600-page biography. But in a way, that’s not surprising. He was the master of paradox, of being not one thing or another, but both. He was such a lover of life and yet does seem to have embraced a kind of martyrdom. He was fascinated with the Christian martyr Saint Sebastian (as am I).

He’s a brother. What can I say? I feel close to him, but sometimes I don’t understand him and find him irritating and frustrating.

As an artist, unfortunately, I don’t think he ever quite reached maturity. He wasn’t given the chance. Had he not had his life ruined by the censorious English society of the day, he likely would have produced truly great work in his forties and fifties. As it is, though, it seems his greatest creation was himself. That seems very modern, in the age of the Kardashians, the selfie and endless self-promotion.

Are you going to give this biography a star?

Two stars! This is a first-rate biography, beautifully researched and written. Wilde is such a towering symbol in the gay world, and I think we should make an effort to know the truth about him. This biography is probably the best place to start with that. I’m just the tiniest bit embarrassed that it’s taken me so long to get around to reading it. It was a thoroughly engrossing literary experience. I’m now going to read more of the man’s own writings.

Write a comment