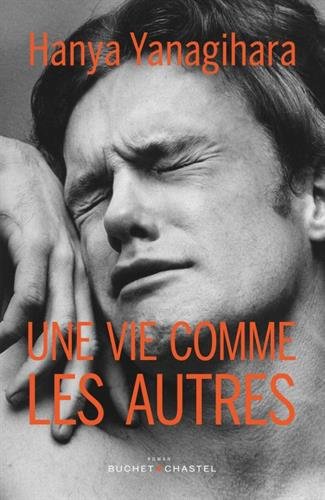

Cover of the French edition of A Little Life (which I like because it shows slightly more of the guy's head). This is a rare case where I prefer the American cover of a book (the American cover has this same image) to the UK cover.

I read a lot, and I don’t write on this site about everything I read. For instance, I read (reread, actually) Nicholas Nickleby earlier this year. As that is not remotely an LGBTQ novel, I didn’t write about it. Others have written volumes about Dickens’s novels.

I recently read A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. I’m not saying I wouldn’t have read it if I hadn’t thought it was “queer,” but I hesitated to launch myself into a book of 800+ pages by an author I didn’t know. What tipped the scales for me were two things: (1) I saw this book on several people’s lists of Best Gay Novels; and (2) it has a quote on the back by Edmund White, which is usually a surefire sign that the book is Gay and Good (or at least serious).

Having now read the whole thing, I would respectfully point out: this is not a gay novel. It does live up to the second of the adjectives I associate with an Edmund White blurb: it is good (or at least serious). But it is not gay.

Spoiler alert: I’m going to have to reveal some plot points, and a lot of the pleasure of this book for me was the fact that I couldn’t see where it was heading, so if you haven’t read it and think you might, you should not read any further.

As I read through the first few hundred pages of A Little Life, I was wondering what on earth was qualifying this as a gay novel. Sure, one of the secondary characters was gay, but the book didn’t focus on his sexuality as a major element, or even on him as a major character.

Then, almost halfway through, I got to the love story. Let’s be clear: while it is indeed a same-sex relationship, one of the characters is heterosexual and the other one is, for the most part, asexual. Willem’s love for Jude is essentially a brotherly love—intense and all-consuming, but a brotherly love. As Willem says to his agent, “I don’t really think of myself as gay.” That’s because he isn’t. As a guy who loves sex, though, he tries to add it on to the relationship with Jude, but that doesn’t work. Jude has always had sex with men, but as he himself says at one point, it’s all he knows; whether he’s actually attracted to men has always been beside the point, because they’ve consistently forced themselves on him (as Willem is doing).

For what it’s worth, the men who are clearly attracted to men in this book are, almost without exception, pedophiles and psychopaths. The exception is Jude and Willem’s friend JB, who is neither of the above but is messed-up and self-obsessed and seemingly incapable of a long-term involvement. I kept wishing that Jude, who is an unforgettable character, was really gay and that he’d meet a loving gay guy. But in the end, he has to be “saved” by a straight guy.

But then, maybe Jude’s straight too. Towards the end of the book, as Jude imagines what his life might have been if he’d had a normal childhood, he pictures himself as a teenager, with a girlfriend.

So.

In one respect and one respect only, I’d put this in the same category as that “great gay film” Call Me By Your Name. Both portray same-sex love involving acceptable men, that is to say, essentially straight men.

I’m mentioning this novel and that film in the same breath only because I think they both portray what you might call heteronormative same-sex relationships. The big difference between them is that, while I found the film to be resolutely mediocre, this is in many ways a very fine novel. It is one of the most compelling books I’ve read in years—those 800+ pages flew by like the autumn leaves outside my window, or like a Charles Dickens novel—and it contains so much wisdom about human beings and human lives. (I do have a major reservation about the book’s ending, but it’s not relevant here.)

For me, though, as a queer reader, there was a sentence that stood out and indicated a different direction the book might be about to take, but in the end didn't: “[Willem] sometimes wondered if it was simple lack of creativity—his and Jude’s—that had made them both think that their relationship had to include sex at all.” Indeed. A same-sex, intimate but penetration-free relationship in which one partner pursues sex elsewhere with members of the opposite sex would be queer. But Willem is so not queer. He’s the emblematic straight guy. His attraction to Jude is a one-off. What ends up being the fault line in their relationship is the sex.

Looked at through a strictly queer lens, the thing about this novel that I found most compelling was its focus on trauma, and this is a major (perhaps the major) thread of the story. So many gay men carry trauma in our bodies, and the part of the book (a couple of hundred pages) in which Jude tries to reach through his own trauma in order to move forward into love and intimacy is beautifully portrayed, and heartrending, and unforgettable.

I loved most of this book, and would highly recommend it. Reading it is an experience; you might even feel yourself growing and changing in the process, as if you’re living “a little life” as you go. But to suggest it’s a novel about gay life is like saying one should read Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot novels to understand what it means to be Belgian.

Write a comment

Niaz (Monday, 10 July 2023 19:28)

Are these full noel?